Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth (SIBO) is a condition defined by an increase in and/or an alteration in the type of bacteria present in the small intestine. It is characterized by bloating, belching, abdominal distention, pain, diarrhea and/or constipation, especially following the ingestion of sugars, starches, fiber, and other specific foods.

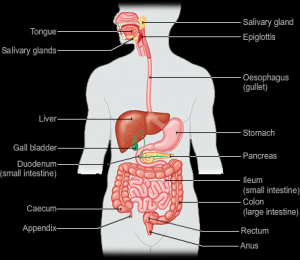

In order to understand more about SIBO, let’s first look at the various parts of the digestive tract and their functions.

Basic Anatomy and Physiology

The small intestine is a 20 foot long tube, about an inch in diameter, that is situated in the middle of your digestive tract. Its function is to absorb viable nutrients from the food you have eaten.

The path food takes as it progresses through the digestive tract is as follows:

Food enters your mouth. You chew the contents. Enzymes in your saliva begin to mix into your food and breakdown the food along with the mastication of the chewing. This is actually where digestion begins.

Food enters your mouth. You chew the contents. Enzymes in your saliva begin to mix into your food and breakdown the food along with the mastication of the chewing. This is actually where digestion begins.

You swallow the chewed food which proceeds down your esophagus, into your stomach.

The stomach lining secretes Hydrochloric Acid which has a number of functions. It helps your body begin the process of digesting proteins. It acidifies the contents of the stomach to prepare it for emptying into the small intestine. And, it acts as a first line of defense to kill off pathogens such as bacteria and parasites that enter through the mouth, typically on or in food.

When the contents of the stomach become acidic enough, they empty into the small intestine where they mix with additional digestive enzymes and move along approximately 20 feet of winding tube-like structures. On a microscopic level, inside the small intestine, are cells that make up the brush border of the intestinal lining. Their main job is basically to absorb nutrients from your food so they can be used by your body.

Eventually, the “food” makes it’s way through the small intestine and into the colon, also known as the large intestine, to be prepared for elimination. Then, out it goes.

Bacteria’s Role in SIBO

The small intestine is essentially pretty sterile, meaning the bacterial content should be fairly low. That would be in contrast to the colon, where bacterial counts are relatively high. But in the SIBO patient, bacteria counts abnormally increase in the small intestine, causing complex problems.

The small intestine is essentially pretty sterile, meaning the bacterial content should be fairly low. That would be in contrast to the colon, where bacterial counts are relatively high. But in the SIBO patient, bacteria counts abnormally increase in the small intestine, causing complex problems.

For one, the extra bacteria interrupts the normal course of digestion, leading to the bloating, distention and pain the SIBO patient is so used to suffering. In addition, that altered environment makes it difficult for the body to absorb all the nutrients it should, further perpetuating the problem because now the body doesn’t have the nutrients it needs to heal. This becomes a vicious cycle.

It should be noted that the “friendly” bacteria normally present in the small intestine are there, at least in part, to support digestion and assimilation of nutrients. The problems arise when introducing the “problematic” bacteria, as is present in the SIBO patient’s small intestine, which causes the complex cascade of health issues.

For information on what causes SIBO and what you can do about it, see our additional educational articles HERE.